This week it happened to be awful takes on Barbie and Oppenheimer. But truly, most reviews of cultural products are worse than neutral. Reading them poisons the mind. I’ve long had an urge to air the many sins of contemporary reviewers. For a time, I considered writing reviews of reviews. But I didn’t want to be part of the problem.

This is a brief theory of what sucks about them, focusing on book reviews — but it certainly applies to reviews of films, TV, music, performance, etc.

There’s a lot to hate about modern reviews, but the single biggest problem is that reviewers write out of fear. They fear the impact on weaker minds of what they perceive as incorrect messaging in the work. Barbie doesn’t portray the right kind of matriarchy. Oppenheimer didn’t show the Japanese perspective. In both cases, the fear is that others — never the reviewer — will get the wrong idea.

Here’s what I imagine a reviewer proclaiming as they dash their glass of cheap scotch into the fireplace:

O ruined world! Would that this film or book had produced the correct message! That the callow and morally feckless public had been spared its malign influence.

And what is the correct message? In the case of Barbie, Oppenheimer, and every other cultural output, the correct message would have been an earnest statement of the reviewer’s own worldview. This implies a lot of unhinged assumptions about the purpose of art. Apparently, it is to argue in the public sphere a valid — by the critic’s lights — take on whatever the apparent topic of the work is.

I call these annoying reviews second-person reviews. To explain why, here’s my taxonomy of reviews and what they say about different approaches to reading.

First-person reviews

The most unpretentious reviews are left on websites and simply state the reviewer’s own private reaction to the work: love it, hate it, felt nothing.

This is actually pretty good. It reflects an attitude towards art that is sustainable. Rewatch what you love, avoid what you hate. Doesn’t have to be intellectual. Judgements can be on a visceral, interoceptive level. If you stick to this, you can’t go too wrong. It’s a totally admirable aesthetics.

But perhaps you want a bit more strategy in deciding what to consume. You might want to discriminate between what you loved and really loved. Or figure out why you hated something so you know what to avoid. Maybe this sounds selfish or greedy. I hope so. Aesthetics should be mainly about enriching your own life, finding more meaning, sucking the marrow out of it, plumbing the depths of your own psyche, scaling the heights of Parnassus, encountering the sublime, blowing your mind, upending your worldview, challenging your politics, being transported, transferring emotion, melting your heart.

Simple first-person reviews don’t offer much help here.

Second-person reviews

You might turn to professionally written reviews. Sadly, most reviewers care much more about how others will read or view a work. They read from the second person.1

This is deeper water and most critics can’t swim. First, there’s an arrogance that automatically arises:

While I could see through this inferior work, I fear others of a more gullible sort will be beguiled by its superficial charms.

This is another form of the censor’s fallacy:

I could watch this obscene film without bursting into flame, but the infantile general populace will surely be corrupted; better to ban it.

This is almost understandable. At least there is an attempt to think like other people, to imagine that not everyone sees the world the same way, to escape solipsism and the mere projection onto others of your own state of mind. But in this lazy second-person perspective-taking, the imagined other is only ever inferior to oneself. It is unthinkable to the reviewer that their own interpretation was in any way less than other people’s, or that others might have more insights.

Did the reviewer’s own ideas about gender get warped by watching Gerwig’s suboptimal feminist thesis, Barbie? Of course not. They’re immune. But some imagined other, some John Q Shitforbrains, will be infected by the latent ideological virus detected in Barbie’s messaging.

Second-and-a-half-person reviews

Most reviewers also expand slightly beyond the duo of themselves, with their correct view, and an imagined inferior reader. They incorporate the role of the author too.

This was actually looked down upon in literary circles in the post-war years. Monroe Beardsley, in an influential paper called “The Intentional Fallacy,” proclaimed that it was simply irrelevant what an author thinks or says about her work. Roland Barthes further inhumed all talk of intentions in “The Death of the Author” and Michel Foucault asked “What is an Author?” — answer: ils ne sont pas de la merde.2 All these authors are now dead (practise what you preach) and their ideas more so, if we judge by how much time is spent diagnosing the intentions, often unconscious, of writers and directors.

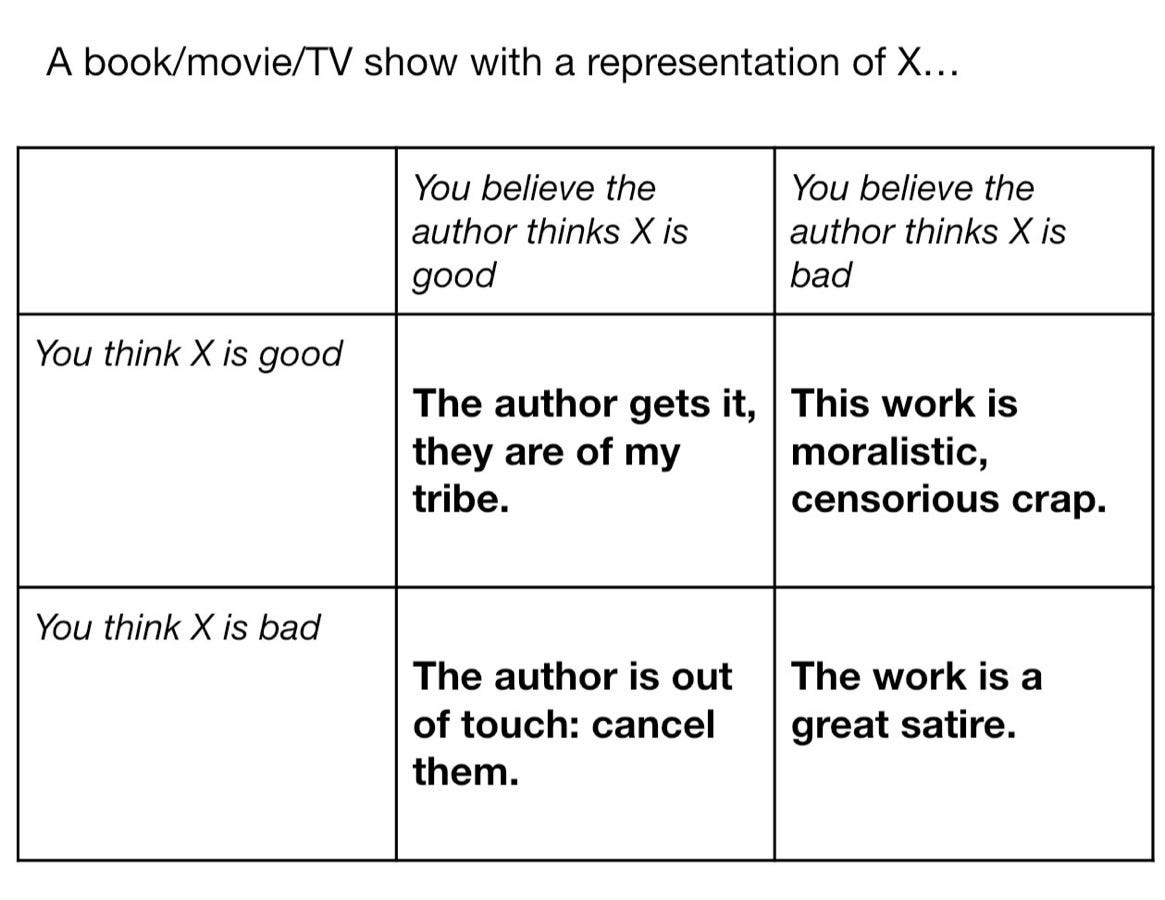

What’s funny is that reviewers assume they can divine the intentions of the author, even in works that are ambiguous (perhaps because the author intended them that way?) The author’s intentions must be aligned with their own. Because they’re certain that the author has an opinion on the theme and that the opinion is unambiguous, they follow something like this table:

Third-person reviews

You might expect me to offer a sophisticated method of reading and reviewing befitting the name third-person. I once read the book How to Read a Book by Mortimer Adler. He advocated “synoptical reading” as the highest level, the most mature way of reading. It is a comparative approach that reads several books on the same theme together. But I’m not going for anything that professional.

My notion of thoughtful third-person reviewing and reading loops back to a first-person approach. A good review is personal. The reviewer can only write from her own perspective. Yes, this is subjective. What if the reviewer’s some freak with taste unlike any reader? This is inevitable.

But here’s the subtle difference between this and the basic first-person review that simply declares, “I loved it”. If the review gives some indication of what kind of person they are, and if the reader also has an ounce of sensitivity, then it is possible to reach across the gulf of separate selves, of two readers trapped in their skull-sized kingdoms, and indeed across the gulf of space and time involved in any act of reading. The reviewer doesn’t have to drop a quick memoir at the top of each review. They need to express how they felt rather than being sidetracked by what others might or should feel about the work. The more truthful it is about what it made the reviewer feel, the more useful it is for the reader.

The reader doesn’t need to be told it’s a personal opinion. What else could it be? So it won’t matter if they disagree with the reviewer. The reader of the review, so long as the reviewer was candid, will be able to imagine what the work is like, what the reviewer is like, and reflect on what they themselves like. This is, grammatically, a first-person review, but one which respects its readers as being first-persons as well.

Admittedly, most readers of reviews may not want this. There is demand, it seems, for the dominant type of dumb second-person review. Many readers apparently want guidance or permission to denounce what should be denounced and to applaud what should be applauded. These are both public reactions, they concern what the community has decided is acceptable or not: the party line. But if you cannot have a private, personalised reaction to art you are in danger of losing your personhood. As Shoshana Zuboff says, “If you’ve got nothing to hide, you are nothing.”

A final complaint

A lot of reviews are shit because they focus on what isn’t in the work. These reviewers pine for an alternative universe where a book covered everything they already thought about a topic and nothing more or less. They yearn for a scene in a film where the protagonist turns to the camera and declaims a short speech articulating the reviewer’s latest opinion.

This happens for all genres but is rife in nonfiction book reviews, which often spend the majority of their words on what a book left out. This is profoundly idiotic. Putting to one side glaring omissions of subject matter, any book necessarily leaves out almost everything.

Focus on what is in the book. In fact, the best aspect of most reveiws is the summary. This is the least spicy section and the least interesting for the reviewer to write, I’m sure. But it’s the most useful for the reader.

Amazon reviews are often hellish but there are also thousands of amateurs out there doing a much finer job than the professionals. They prove that a snappy 400 word review of a big book is possible. 200 words on what’s in it (something more accurate than the publisher’s blurb) then 200 on why it was or wasn’t worth the reviewer’s time. Which, as I recently wrote, is the gold standard of all reading and writing and, well, everything.

The saddest fact is that even good (as in not great, just good) works aren’t quite worth our time. My god. Only if we lived an extra hundred years or so could we ever say it was worth reading or viewing anything other than the most rewarding and special things.3

Appendix: How to live without ever reading a book review again

The most efficient way to avoid reading inane reviews is to never read any reviews at all. How will you know what to read? Well, if you don’t care about keeping up with very recent books, I offer the following bonus reading plan (for fiction) that is highly robust.

Call this simple algorithm Repeat200:

Take the top 200 novels according to some vaguely respectable list or other from the Internet (or smoosh a few lists together).

Start reading somewhere in the list. Don’t worry if you don’t like some of the books — discard them. You don’t even have to finish each novel.

Don’t read any novels not on the list (except in extenuating circumstances like for a course or book club or your mother publishes one).

Keep going until you’ve tried all 200.

Now go back and reread the ones that moved you.

Repeat step 5 until death.

This simple algorithm is guaranteed to beat 90% of reading strategies. To do better than Repeat200 requires a fair amount of time in planning a more nuanced approach. If you run the Repeat200 algorithm, you’ll spend whatever chunk of your life you want reading true masterpieces. And you will have eliminated all the wasted time of reading the paltry or, more dangerous, the merely good.

Sidenote for those interested in literary theory. There has been what they call a social or political turn to all criticism. To offer any reading that is about personal fulfilment or pleasure — or any formalist reading — is to be apolitical. And to be apolitical is actually a politics of its own, a conservative one at that. Hence, leftwing critics have extirpated this kind of thing from the academy. Not completely of course. In post-structuralist criticism, strains of individualism can be found (this is ironic, given all those ignoramuses who blame everything on “postmodernism” and its presumed alliance to leftwing politics). Barthes wrote (brilliantly, I think) of the pleasure of the text. And for Foucault the work of literature can be a site of resistance, partly because it’s uncontaminated by broader forces of domination. Anyway, I agree that to be apolitical is actually to be conservative: it is a deferral to the status quo. And I agree that some literature has a political effect (most books don’t, but occasionally you get a Harriet Beecher Stowe, or Alexander Solzhenitsyn, even Margaret Atwood), unlike visual art which seems to have none. (Robert Hughes agrees with me here in this clip from The Shock of the New). But most books aren’t like Uncle Tom’s Cabin, they don’t change the world in any provable way. This is because rhetoric simply doesn’t work as much as people think it does. The power of words isn’t magical: merely printing them doesn’t cause their message to be influential, to change minds and actions. I’m not against political readings or political writings. And I am vehemently anti-conservative. I just think that if you want to take political action, writing a novel about some cause can have an impact but it’s a long shot. And in any case, your readers aren’t obliged to change their politics or read it politically. It’s entirely up to them how to read it. Which I take to be an antiauthoritarian reading practice and hence the opposite of conservative.

Anyway, my rhetoric right now won’t convince anyone either. But reading and rereading a great text will change you even if only for the duration of the reading, in which you will have larded that time. You might even be reminded, during the act of reading, of what some Greek philosophers thought was the true object of all art: to demonstrate the materiality of time; the palpability of passing existence; aisthesis. The only modern critics I’ve seen properly get into this were old mate Russian formalist Viktor Shklovsky, and the classicist James Porter whose scholarship is outstanding.

Roughly: They ain’t shit.

Obviously, my spirit is willing, my flesh weak, so I’ve broken this rule. But I’ve paid real attention to what I’ve read and tried to not read a lot of things I otherwise might have. Over the years I’ve conducted a series of reading audits and I’ll write a post about that soon.

This is broadly excellent but I worry that it will encourage a society in which people will give less importance of place to critics.

I LOVE THIS SO MUCH, Jamie. I recently wrote about a similar thing, namely the perpetual disappointment that circulates around the 'poor' quality of reviews because non-experts seem to be writing them: https://www.griffithreview.com/articles/reading-the-room/.

The idea of some conformist, authoritarian approach to reviewing really bugs me, precisely because it pretends we don't (or shouldn't) respond to texts in any individual (and non-intellectual) way. I'm supposed to be writing something now about censorship of literature, and this line probably sums it up: 'The power of words isn’t magical: merely printing them doesn’t cause their message to be influential, to change minds and actions.' I've been freaking out about my take. It's keeping me up at night. So reading those words brought me some comfort. (And I just recommended this newsletter to an artist friend who's researching AI and EMS-enabled tech.)